By Andrej Koymasky

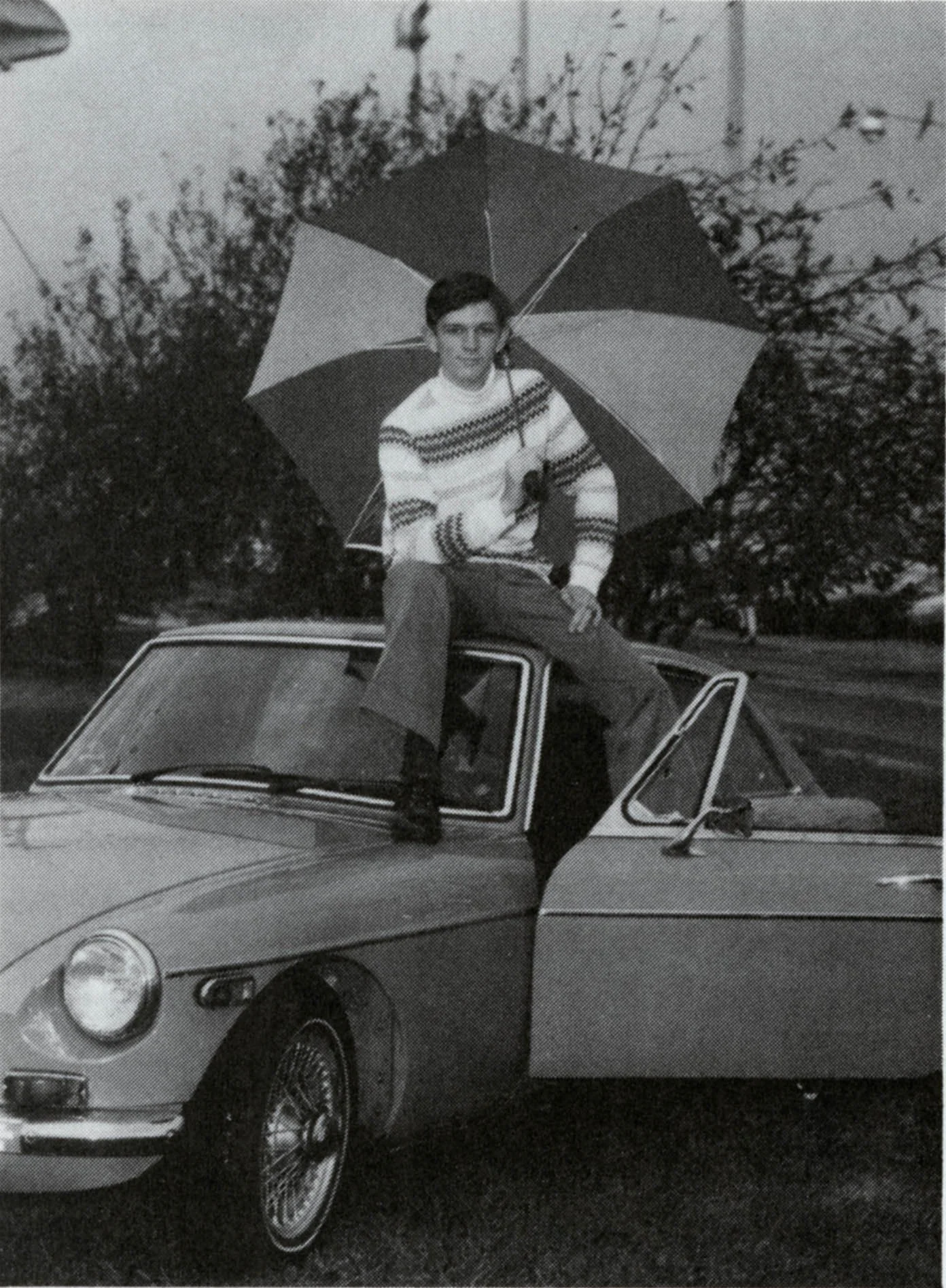

Berg graduated from the Naval Academy at Annapolis. He was called Copy because he was so like his father, Commodor Vernon E. Berg Jr., one of the most respected officers in the Navy's chaplain corps. Their childhood photographs were indistinguishable. As young Vernon grew into his full 5-foot, 9-inch frame and his hair turned sandy blond, he was still the carbon copy of his dad, right down to the deep blue eyes and second-tenor voice, which was why they called him Copy. And they were extraordinarily close, to the point that Copy knew what his father was thinking just by looking at him, as if they were the same person.

Norfolk Naval Station had the nondenominational look of all military installations. On a January morning in 1976, however, it was clear by the number of reporters descending on the place that something important was happening. Inside, an administrative board took up the case of Ensign Vernon E. Berg III, the first officer in the history of the Navy to say he was a homosexual and wanted to stay in the military.

While the attorneys dug into their law books, Copy worried about whether his father would make the trip to Norfolk when the separation hearing began. His lawyers were unanimously opposed to having the senior Berg appear. No one was sure what he would say. He could hurt Berg's case if he came down on the side of the antigay regulation.

Copy did not think his father would hurt his case. On one level, he appreciated the significance of walking into the hearing alongside his father, a career Navy man like those who would be judging him. This, however, was an almost trivial consideration in comparison with the main issue. He could stand losing his bond with the service, but he could not stand losing his father. It would be like losing a part of himself.

The climax of the eight-day hearing occurred the next morning when a Navy commander took the stand. His dress blue uniform only highlighted the striking resemblance the man bore to the defendant. On his chest, among all the other ribbons Commander Vernon Berg, Jr., had accumulated during the course of his career, was the Bronze Star he had won when he almost died ministering to Marines during the Tet offensive. In the middle of the red, white, and blue ribbon was the letter V - for valor. Berg's Navy lawyer, Lieutenant John Montgomery, asked the chaplain about his experiences with gay sailors

"A person is a person," Commander Berg began. "I really have felt strained in this whole hearing about people saying homosexuals have different problems. They have the same problems as anybody else. A homosexual can perform badly or spectacularly well. Homosexuals that I have known in the military have done extremely well, getting to extremely high ranks after I first met them."

"Are you saying that you know of homosexuals who are officers in the United States Navy today?" Montgomery asked.

"Certainly," the chaplain answered.

"Do you know any of them of the rank of commander?"

"Certainly."

"The rank of captain?" Montgomery asked.

"Certainly."

"The rank of rear admiral?"

"Yes, sir," Berg said. The room fell utterly silent while the chaplain continued. "Therefore, I would like to interject that I think it behooves all of us to look at what we do. We condemn blindly with prejudice and, you know, we must be careful whom we condemn."

When Montgomery asked about Berg's experience as a chaplain to Marine units in Vietnam, the commander said that at least once a week one or another Marine would come to him and admit to being gay. He also acknowledged, somewhat painfully, what he would have done not too long before if a commander had sent him a gay soldier.

"This week has been a learning experience for me," the elder Berg said, "and I'm sure it has been for all of us. I'm a product of Navy society also, and, sadly to say, years ago in 1960, '61, '62, I would have told him carte blanche, 'If you are a homosexual, you had better get out'."

The world was changing, he added, looking toward his son.

"We are advancing into an age of enlightenment. Hopefully, that will make such inquisitions unnecessary in the future."

The elder Berg walked down the aisle of the hearing room as Lieutenant Artis began reading from the Navy's regulations on homosexuals again: "Under 'Policy,' paragraph four, it's very clear, very insistent, the way I read it...."

The voice faded into background noise as Copy watched his father walk from the stand. Commander Berg had rarely discussed his Vietnam experiences, and now Copy could see why. A part of the chaplain still grieved for the dying Marines he had held in his arms. Copy had never seen his dad so emotional; he had never seen him so mortal; he had never loved him more.

When Copy focused again on the proceeding, he was consumed with resentment that the officers could so roundly ignore what his father had just said and so easily slip back into quoting SECNAV instructions. There were many things that would long anger Copy Berg about the hearing, but nothing more than a board that asked a man to resurrect the most painful moments of his life and then answered him with quotes from a rule book.

There was a second painful understanding Copy came to that day. He had learned for the first time what his father thought of homosexuals there, in a hearing room in answer to a lawyer's questions, because he had not had the courage to ask such questions himself.

Copy got an "other than honorable" discharge as an ensign, because investigation revealed he was in a gay relationship. He was one of the first military officers to challenge a discharge on the ground of homosexuality. After his discharge, Berg received a master's degree in design from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

In 1978, the U. S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that Berg and former Tech. Sgt. Leonard P. Matlovich of the Air Force had been unfairly discharged, although it did not reinstate them, as both had sought. After Copy's suit against the Navy, the armed forces adopted a policy of generally granting honorable discharges to homosexuals. Vernon's father, who supported his son's legal battle, died in 1984.

In recent years, Berg attracted attention anew as a prolific artist who documented life with AIDS in sculptures, paintings, photographs and thousands of cartoonlike drawings in hundreds of sketchbooks that he called the "pages of my unfinished Surrealist novel."

In 1998, Berg was embroiled in controversy again when some students at Rutgers University objected to the sexual content of some photographs taken by Marcus Leatherdale, of Copy and his previous partner, Paul Nash, who died in 1993. Eight photos, six of which depicted Berg nude, accompanied a show of his artwork in a gallery on the Newark campus. One of them showed Berg masturbating.

"They don't see AIDS as relevant to them," Copy told in an interview. "I presented masturbation as an alternative to a death sentence. They thought I was just showing off."

He was one of the first to stand up to the military, said Kevin M. Cathcart, executive director the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, which represented Berg.

"People forget in the 1990s what kind of courage that took. Tens of thousands of people have benefited from his fight."

Copy lived in Manhattan and Bridgehampton, N.Y., with his last partner, Dub Williams. Vernon E. Berg III died at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan of AIDS related complications.